Monday, November 16, 2009

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Monday, October 19, 2009

Skating as an Adaptaion of Space

The built environment is made up different systems and components (roads, factories, residencies, shipping yards, restaurants, tunnels bridges, etc.) which functions as avenues and settings for the people, activities and mechanics of a city. As the activities and demographics of a city change over time, elements of the urban fabric are used differently: some are retooled and redesigned to accommodate the changes, others are destroyed forever and still others are abandoned as they are. Abandoned urban spaces can take the form of empty, derelict factories, underpasses and outdated service tunnels but can also be empty plazas, back alleys, scraps of space in-between buildings and expansive parking lots which have, for one reason or another, fallen into disuse. Before long, these spaces, ignored by the city and it’s intended users will attract new users: scavengers of space.

Street skating is rooted in the reapportion of urban spaces like these. Skateboarders use the armature of the city, which once served a bureaucratic or civic purpose, and utilize it for it’s physicality: exploring their very floors and walls (as slopes, ledges, curbs, dips, gutters and steps) and their street furniture (like handrails, benches, trashcans, tables, etc.). While skateboarding is often looked at by city officials and property owners as a public nuisance and frequently banned in public spaces, street skating as a civil act is integral in the adaptation and reuse of spaces which have become obsolete.

Reforming the Hell-Hole Home

Dark, dank and crowded a small child shares a bed with her 8 siblings. In the morning she will continue her work making fake flowers for hours on end with these same siblings. Making pennies a week, she contributes to large the family’s small home. Like many lower-class families of the 19th and early 20th century, tenement housing was a necessity that sacrificed comfort simply because they had no alternative considering their class, income and in many cases ethnic background. Tenement living in the 19th and 20th century had acute equivalency to that of a death trap. Along with over-crowding, lack of necessary utilities, was the threat of infectious disease and overwhelming structural danger. With the crowding that came with robust immigration, and an industrial upturn was the absence of a planned and moral way in which to house these masses. Eventually recognizing the error in the living conditions of the poor, reform was afoot, but never quite successful as it set out to be.

Sunday, October 18, 2009

Unwelcome West: The Dust Bowl's contradiction of frontier prosperity

In 1936, John Steinbeck visited squatters’ camps in California. His observations of this population of refugees from the Great Plains Dust Bowl vividly depict the horrors of their living conditions:

The next-door-neighbour family, of man, wife and three children of from three to nine years of age, have built a house by driving willow branches into the ground and wattling weeds, tin, old paper and strips of carpet against them. A few branches are placed over the top to keep out the noonday sun. It would not turn water at all. There is no bed.

Such was the life for dispossessed farming families who fled the desolation of the Dust Bowl. However, theirs was the popular choice. During the decade of what historians have said was this country’s worst prolonged environmental disaster, two thirds of the population of the southern plains never left their homesteads despite the drought, and then the unrelenting dust that overwhelmed their lives. All told, the Dust Bowl cut a swath of despair that spread from Texas to California, a direct affront to the ideal of the American West. The Dust Bowl and subsequent Californian migration was too much for any western American resourcefulness to handle. In the 1930s, the ideal of the American frontier is firm was still firm in the nation’s psyche. Reactions to the living conditions of Anglo-Americans in the Dust Bowl and the migrant camps of California, notably the journalistic documentation of them, clearly illustrate that power.

Be Seen

BE SEEN

Every year thousands of people in New York City wait anxiously for the month of September to arrive so that they are blessed with the presence of that year’s fashion Bible (Vogue September issue) and the masses of fashion designers that make their way to the tents of Bryant Park for New York’s Fashion Week. This much-anticipated phenomenon seems to be only taken seriously in New York and because of this, it has been labeled as one of fashion’s iconic cities. In order to understand how this city has been able to attain this label, it is important to understand how consumerism has shaped the built environment of New York City. Examining the investments that people made in order to create shopping malls and other shopping venues and their goals behind supporting the idea of ‘consumerism’ is critical to understanding the way in which people ultimately look at fashion as an investment and a way to be seen within this city. Within the built environment, being able to analyze the motives and creative processes behind the designs of the buildings and the accessibility of main streets and commercial areas is important in order to promote and facilitate commerce and institute a desire for people to be there. Zoning in on Fifth Avenue, Soho, and the Meatpacking district will show how fashion has shaped consumerism to improve these areas, and simultaneously launching New York into a fashion city that is known to the entire world.

Charleston and the Falsification of the Old South

"I'm going back to dignity and grace. I'm going back to Charleston, where I belong." (Rhett Butler, Gone with the Wind) Rhett Butler's statement is often the way people imagine Charleston, South Carolina to be today; a decadent historical southern city that has not changed since prior to the Civil War. However, this image is very misleading. It is through efforts of historical preservation in the twentieth century that Charleston has been able to emulate a pre Civil War historical appearance. This preservation movement began in the 1920s as a response to the destruction of historic structures in order to accommodate automobiles. Thus, the historical preservation movement lead Charleston to economic stability as a means of “sell[ing] the city... to the outside world” and creating tourism as its main industry.

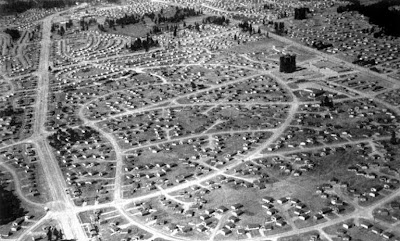

A dream debauched: The decline of individual as homemaker in suburban America

Update: Image uploading seems to be working now so I will add images.

Update: Image uploading seems to be working now so I will add images. America, since its first settlement by Europeans, has developed an intense cult of individuality. In many cases the new settlers were those whose individuality was too strong to allow them to remain comfortably in Europe. They set out to the New World as individuals. Upon arriving, they strode into the woods and individually carved sites for themselves, and, perhaps most importantly, they rolled up their shirtsleeves and began building their own individual houses. This notion of the heroic individual-builder played a major role in establishing another great American ideal, that of the utopian pastoral community. For the first 250 years of European settlement in America, development and expansion were seen as a social panacea. If deserving and upright Americans could acquire their own homes, the thought was, they could surely achieve the ideal of Protestant morality to which the country aspired. Yet gradually this aspiration fell apart. By the 1960s and 70s Americans were starting to see the shortcomings in their grand suburban dreams which had somehow fallen short of the ideal community they were supposed to foster. And while there are certainly numerous factors behind the gradual debauching of the American suburban ideal, the diminishing of the individual’s role in home selection and construction can be traced along a parallel trajectory.

America, since its first settlement by Europeans, has developed an intense cult of individuality. In many cases the new settlers were those whose individuality was too strong to allow them to remain comfortably in Europe. They set out to the New World as individuals. Upon arriving, they strode into the woods and individually carved sites for themselves, and, perhaps most importantly, they rolled up their shirtsleeves and began building their own individual houses. This notion of the heroic individual-builder played a major role in establishing another great American ideal, that of the utopian pastoral community. For the first 250 years of European settlement in America, development and expansion were seen as a social panacea. If deserving and upright Americans could acquire their own homes, the thought was, they could surely achieve the ideal of Protestant morality to which the country aspired. Yet gradually this aspiration fell apart. By the 1960s and 70s Americans were starting to see the shortcomings in their grand suburban dreams which had somehow fallen short of the ideal community they were supposed to foster. And while there are certainly numerous factors behind the gradual debauching of the American suburban ideal, the diminishing of the individual’s role in home selection and construction can be traced along a parallel trajectory.Saturday, October 17, 2009

The Museum As Art and Philosophy

Visual art is often defined by the space in which is found. It can be contained, protected, and kept captive by the space; or it can be let free into the open air to truly be experienced, and the organic nature of its presentation becomes part of the viewing itself. The emergence of the public museum in the American city was a physical manifestation of the shifting national attitude towards art. Art was once a thing restricted only to the educated upper classes. But the museum movement beginning in the early 19th century introduced the idea of art as a public commodity, something that should not be hoarded away in dark halls but displayed for the education and betterment of the general population. This philosophy of art made available for the greater good is made plainly apparent by the multitude of public museums now present in American cities, and in the design philosophies of the architects contracted to build them.

Victory Gardens for the 21st Century

In the later half of the 19th century, urbanization was a sign of progress. But as land was developed and millions left the country for the city, feeding the nation was left to fewer farmers on fewer acres. During World War II, because of the threat of food and fuel shortage, 20 million Victory Gardens were tilled in non-rural areas. Today, especially in its cities, America faces a serious shortage of healthy, fresh produce in addition to many other social and environmental problems. The Victory Garden movement can be used as inspiration for the current promotion of urban agriculture. America is fighting a different war now, a war on hunger and malnutrition, joblessness, and environmental degradation, but this war is taking place within our borders. Only by approaching the challenges we face like the Victory Garden movement of World War II, will Americans be able to reshape the urban landscape so as to sustain a healthy population.

A Slow Reconciliation: Yale’s Expansion and its Impact on Town-Gown Relations

In the early morning hours of February 17, 1991, a gunshot disturbed the New Haven chill. In the turbulent, drug-riddled years of the 1980s and early 1990s, that was a tragically common occurrence for the city. This particular gunshot, however, attracted the attention of the city and, indeed, the country, because it resulted in the murder of Christian Prince, a nineteen-year-old Yale sophomore. Testimony by his would-be accomplice—although still contested—named James Duncan Fleming, a local youth, as the murderer. Reportedly, Fleming had demanded only money from the Yale student, but still decided to murder him after Prince relinquished his wallet willingly. Fleming, who is black, is said to have mused “I should shoot this cracker” before directing his gun at the white, and privileged, Prince. Christian Prince’s murder served as not only a tragic shock to the entire Yale community, but also a spark to set off unprecedented dialogue about race relations and town-gown relations in New Haven. For nearly a century preceding 1991, Yale’s growth and expansion had been unchecked physically and mentally; rather than the symbiotic relationship which the university and the city had once pursued, Yale became one of the world’s foremost universities and left New Haven abandoned in its dust. The opulent gates of the ivory tower remained permanently closed to most members of the New Haven community, and the distinction between the privileged “haves” of Yale and the destitute “have-nots” of the struggling, post-industrial city had never been clearer. Christian Prince’s death cannot be viewed as anything other than a tragedy, but it does seem to have compelled Yale to work to revitalize this decaying relationship. Nearly twenty years later, town-gown relations have recovered a bit from their low point in the early 1990s. The major reason for this improvement seems to be Yale’s less self-centered attitude towards expansion. While Yale had pursued its earlier expansion at the detriment of the city, the two now work in conjunction to allocate land, resources, and tax money. Although the complexity race and town relations cannot be fully explained by any singular factor, the correlation between those relationships and Yale’s attitude towards expansion are striking, and can teach a tremendous amount about the connection between physical and psychological development.

Sarah Landers

Park on the Railroad: Bringing the Twenty-First Century to the High Line and New York City’s Meatpacking District

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

“Parks are our town-hall meetings. We disrupt them, with shows of contempt, or little displays of impishness, for the same reasons that protesters tote AR-15s instead of talking about PPOs: to wrest a bit of control. The thrill of sullying pristine environments—of planting a handprint in freshly laid concrete—is particularly acute in those precincts in which there aren’t many pristine environments left to sully.” Lauren Collins, The New Yorker, 14 September 2009

Three years ago, an area of the West Chelsea neighborhood in New York City was industrial, dirty, and covered with graffiti. A decaying iron railroad dominated the landscape. Today, in that same area, the young and the fashionable mill about. Stores and cafes abound. A trendy, newly opened hotel brags that it is located “in the heart of downtown Manhattan’s meatpacking district.”[1] What happened?

In 2006, construction began on the High Line, an industrial railroad that was built in the 1930s, totally abandoned by the 1980s, and, in the past three years, reborn as an urban park. The site, which runs from Gansevoort to 34th street between 10th and 11th Avenues, makes no pretense at concealing its past: the iron frame of the railroad remains exposed, but it now supports gardens and benches instead of rubbish and undergrowth. The High Line project has renewed the elevated railway, but has also prompted shops, clubs, hotels, restaurants, and museums to come to the area. The revitalization of the High Line as an urban park is the last step in the gentrification of New York City’s meatpacking district.

--Erica

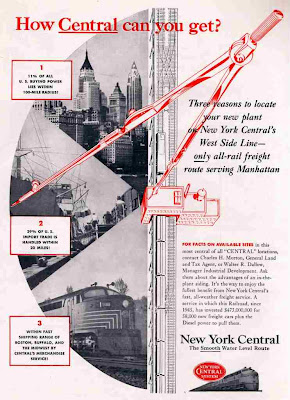

The Politics of the Interstate Highway System

With the passage of the Federal Aid Highway Act

The use of the images wasn't completely explained by the introduction, so here is a quick rundown of how they will be used. The first image shows the sheer size of interstate highway infrastructure and its ability to facilitate the nearby suburban development. The second picture shows the construction of the Route 34 Connector in New Haven and its selected route through one of the city's poorest neighborhoods, and demonstrates the political nature of route placement. This idea is also expressed in the third photo, which is a map of a portion of the New York State interstate system. In the center of the photo is I-88, which is one of the least traveled interstates in the United States, chiefly because it runs only between Albany and Binghamton - cities between which there is not a great deal of traffic. It was constructed under political pressure from a powerful Binghamton Congressman and adds little useful value to the interstate system in New York. The final photo of the construction of I-95 through Richmond, VA demonstrates the destructive power of highways as they cut across cities and, once again, addresses the issue of route placement through poorer neighborhoods.

Remembering Race: a Study of Atlanta's Sweet Auburn District

The street that John Wesley Dobbs referred to as “paved in gold”[1] is now paved with 160 condominiums and lofts and 27,000 square feet of ground floor retail.[2] Needless to say, the Auburn Avenue in Atlanta, Georgia that Dobbs knew in the first quarter of the 20th century was a different world from the development that exists there now. A vibrant center of African American culture, business, and social history during the early 20th century, the Sweet Auburn district situated along downtown Auburn Avenue was an iconic location for Southern blacks and home to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. [3] However, racial implications of the United States South placed the Sweet Auburn district in a world set apart from the rest of the city of Atlanta. Beginning around mid-century, the district started to decline as people moved out of the city center and highway construction moved in and split the neighborhood in two.[4] In 1976, the National Park Service declared Sweet Auburn a Historic Landmark, and soon after it was designated as a threatened historic place.[5] Today, Renaissance Walk, a recently completed redevelopment project takes over a major corner of Auburn Avenue, claiming to foster a cohesive atmosphere within the district and celebrating its new possibilities. One finds, however, through careful examination of the original decision to designate Sweet Auburn a historic district and the presence of developments like Renaissance Walk within the community that Atlanta (and the government) have chosen to remember Sweet Auburn in a very specific way – or more simply, not to remember it at all. The embedded beliefs regarding race in the South mean that the Sweet Auburn district has been historically disregarded and avoided, causing it to now be seen not for its cultural richness or social importance but for its ability to be redeveloped for profit.

Friday, October 16, 2009

The Model City, Round II: Redeveloping New Haven Beyond mid-20th Century urbanism and into the 21st Century.

1- A slide from Major DeStefano's 2008 presentation on Future Framework for New Haven

2- Rendering of the winning bid for the Coliseum site

3- Two areal images comparing the Oak Street Area before and after the construction of the Oak Street Connector

4- Photograph of the vibrant Oak Street Flea Market before demolition.

New Haven of the 1950s and 1960s was an urban planner's heaven with more funds per capita channeled into major urban redevelopment projects by federal authorities than in any other city in the United States. The resulting Model City, however, was far from being a vibrant urban community and the city's inevitable decline was only accelerated through the attempts that inflicted deeper scars in the urban fabric through projects such as the Oak Street Redevelopment Project. Today, acknowledging the failures of the Oak Street Redevelopment Project, city officials attempt to initiate a second wave of planned urban development that will aim to reinforce the first signs of revival in the city after decades long decline. To this end, the demolition of the Coliseum, proposed replacement of the Oak Street Connector by a pedestrian friendly avenue and related large scale real estate projects to the Southeast of central New Haven such as the 360 Park Street and the "Tenth Square" in the Gateway area attempt to reunite fragmented neighborhoods and connect the city with the sea shore once again. Yet with such attempts come also the questions of attainability of grand urban ideas through large scale urban development approaches and the extent to which these new projects draw upon a critical analysis of New Haven's experience in the 1950s and 1960s. An examination of the rhetoric used for advancing the second wave of development projects based on an assessment of the reasons for past failures, suggests that the fate of the new projects may be better than that of the Oak Street Development Project. This, of course, holds only if the outcome of the proposed projects succeeds in realizing the ideas recognized in their promotion, and more time is necessary to assess the real impact of these projects.